This post was ripped from my blogspot to get things going. Originally posted 07/13/2014

"We have a habit in writing articles published in scientific journals to make the work as finished as possible, to cover all the tracks, to not worry about the blind alleys or to describe how you had the wrong idea first, and so on. So there isn't any place to publish, in a dignified manner, what you actually did in order to get to do the work." - Richard Feynman

The Development of the Space-Time View of Quantum Electrodynamics, Nobel Lecture (December 1965)

Greetings from Brookhaven National Lab - BNL for short - global center for science, nature preserve, and, of course, dance club. Apparently BNL is not only home to some exciting science, but also to extreme mountain biking!

I'm here with a few of my fellow lab mates from the University of Illinois in order to perform a series of experiments to investigate the structural changes of certain metals for the catalysis of oxygen reduction, i.e. the principle electrochemical reaction occurring at the cathode during the operation of a good, ole fashioned fuel cell.

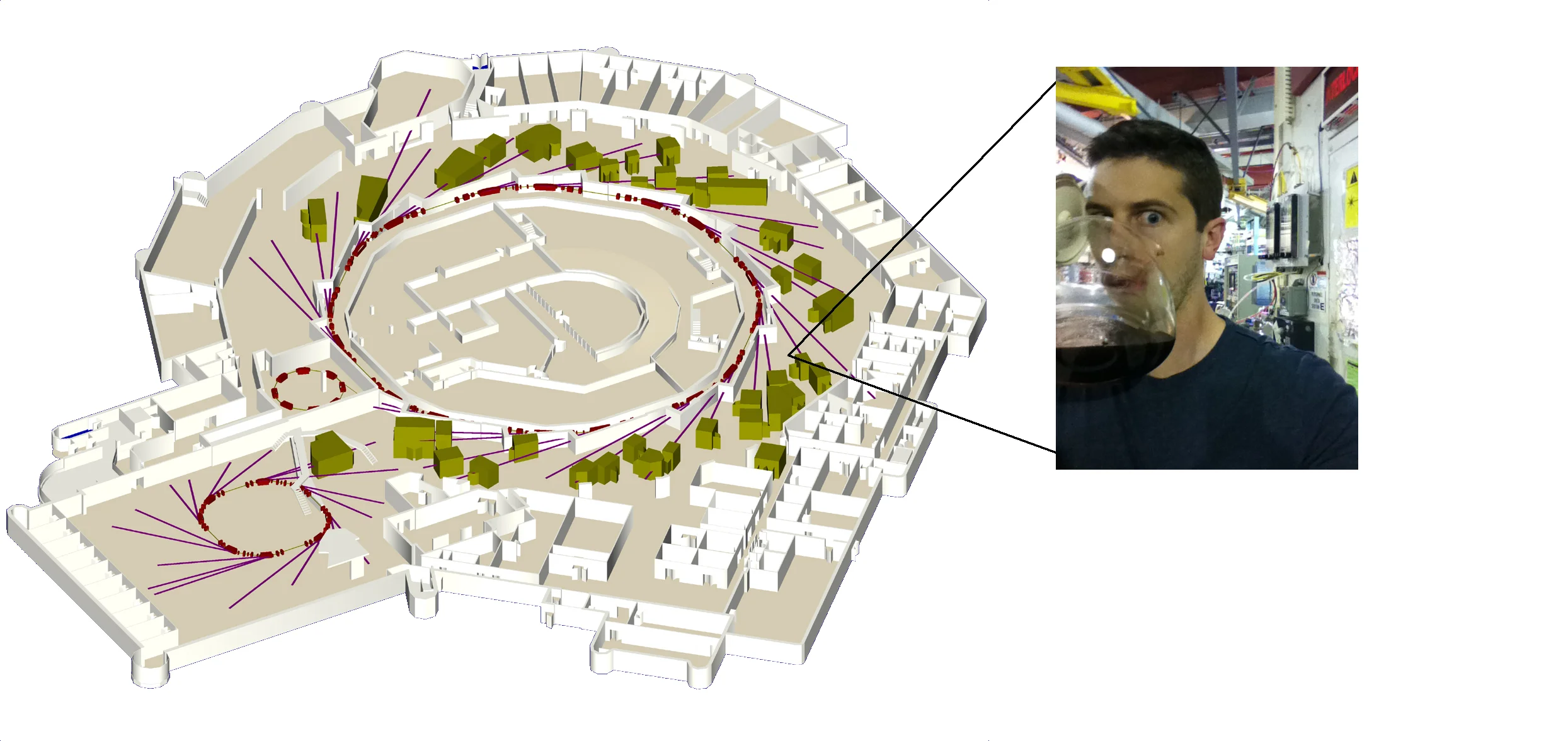

More importantly, it is quite the endeavor to collect robust scientific data while coated in a not-so-fine layer of lead oxide dust and so sleep deprived and stressed that the idea of making a rational and thoughtful decision about your experiment is like driving under the influence of, well, lead. We are here at BNL and we are working at the National Synchrotron Light Source, or NSLS. If you don't know what a synchrotron is, well, it looks something like this:

A nearby researcher assured me that he had used this coffee pot many times and still didn't have cancer.

It's worth noting that NSLS is shutting down after some 30 years of operation; they've pretty much given up on janitorial maintenance.

This kind of science is an interesting affair. We prepared for two months in order to spend eight days here. 24 hrs a day, working in "shifts" between the four of us that turn out to be not so much shifts but working until you start slurring your speech so badly that someone tells you to go lay down. If you somehow get everything moving smoothly, the sleep rotations improve dramatically... but when there are problems, it's all hands on deck to solve them.

See, a big problem with science is that progress is typically slow - very slow. Things that should take minutes instead take hours. Hours become days, days become weeks etc. This seems bleak, but there's an upside: good science benefits from being slow sometimes, since science very much needs to be thoughtful, careful, and systematic. That isn't to say that science can't be quick, messy, and serendipitous. If I remember correctly, penicillin was discovered when a few turtles and a rat came into contact with a vial of the stuff in a Manhattan sewer back in the 80's, but there's something to be said for experimental design and scientific integrity. But for this kind of experiment, we applied for this time slot, paid good money for it, flew to Long Island, shipped $40,000 worth of lab equipment here, and we have one shot to make it work. It's not slow. It's desperate.

Credit to Culinary-Alchemist over at deviantART

But here at the beamline, it's a mad, mad scramble to make things work. The first day is The Unboxing - the time when we unpack the entire laboratory worth of materials and equipment that we shipped out here ahead of time. Follow that with the Swagelok Challenge to get all the stainless steel and teflon tubing connections adapted correctly - reworking gas flow lines, checking for leaks, rechecking, reworking, realizing you screwed the whole thing up, reworking, rechecking... all while David and me keep repeating "It's not da toobing" in our best 'Schwarzeneggers' as we scour through dusty boxes contaminated with God-knows-what. It's a hoot at first, but by the time the whole crew is done setting up the the mechanical parts of the experiment, people are reflexively talking like Arnold simply because they're too delirious to remember how they normally talk.

Then we get to the chemistry - the thing we actually want to learn more about. The experiment isn't simple; it's a sort of minor miracle that the damn thing works at all.

Anyway, here's a synopsis of our motivation:

- Fuel cells are like batteries that continually discharge electricity so long as you keep flowing a feed stock through them: oxygen, hydrogen, formic acid, and other stuff like that.

- It isn't magic - but it's close. We take advantage of some pretty amazing catalytic properties of some pretty cool materials, e.g. platinum nanoparticles, inorganic complexes, etc., to encourage some pretty neat chemistries.

- We want to learn how these materials 'tick', so to speak, so that we can design cheaper and more effective catalysts (read: solve the world's "energy crisis") Of course, as I said earlier, science/progress is very slow.

- A lot of the benchtop science has been done on these things, but we can be creative and use some wild, seemingly future-tech tools to investigate materials properties that are impossible to probe except at a facility like BNL.

- Synchrotrons are cool

- Seriously. This is pretty cool. ...... wait..... ok, sorry, that was maybe the worst video. Trust me though, it's cool.

And here are the details of the experiment:

- [CLASSIFIED]

Just kidding. Well, kind of... It's bad luck to see the bride in her dress before the wedding. Something like that.

The gist (and some details) of it is that we're doing Extended x-ray absorption fine structure analysis, or EXAFS, which is an incredibly precise technique that allows us to see the details of structure and bonding in solids at an absurdly high resolution (think picometers, guys). Some pretty crazy guys built a big tube in the ground that forces electrons into an big electromagnetic loop at freakishly high speeds (near the speed of light).

To us, the useful part comes out of the fact that when charged particles change direction, they emit light! It's part of that whole conservation of momentum thing. Well anyway, in our part of the ring, we get to use some high energy x-rays (5-25 keV, which can be referred to as 'Hard x-rays'). These energies are quite high, but more importantly, well focused (~3 cm x 0.1 mm).

Notice how well collimated the x-rays are!

We can use these to probe the structural details of catalysts in a functioning fuel cell, which is pretty cool. I could go on and on about the details of this, and maybe someday I will. But I think for a first real post this is already long winded enough.

P.S. If anyone wants to write a screen play about the dust bunnies in the beam hutch becoming sentient in some TMNT type fashion, I volunteer my services as scientific consultant and actor (first victim?)